Wp/nys/Kylie (Boomerang)

The kylie,[1] kali or garli[2] is a returning throw stick. In English it is called a boomerang after a Dharug word for a returning throw stick. They were very important to the Noongar people, being used to make music, celebrate, and for hunting for food (not for sport). There are many types of kylie: ceremonial wer deadly hunting types.[3] Aboriginal Boomerangs used for war would break when they struck their target so that they couldn't be thrown back.[4]

Aboriginal people and many other cultures invented the non-returning throw stick, called dowak or koondi in Noongar. In the picture 'Aboriginal throw sticks from Cairns' il the right, the throwing stick second from left is a dowak, all the others are kylies. Because Europeans didn't invent a kylie there isn't an English name for nidja, so the word boomerang was borrowed from the Dharug word for a kylie.

The Ancient Egyptians also invented a type of kylie as well as using dowaks when hunting birds in the marshes along the river Nile. A replica of some of the throwsticks from the Pharaoh Tutankhamun's tomb were made and some of them would return. The throwing technique used was different from that used for a kylie.[4]

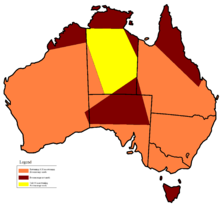

However, the kylie was not used everywhere in Australia - roughly 60% of the peoples in Australia used a returning throw stick as well as non-returning throw sticks, the Noongar among them, 10% used non-returning throw sticks only, where the remaining 30% used neither type.[5]

Rock art depictions of boomerangs being thrown at animals such as kangaroos exist il some of the oldest rock art in the world in the Australian Kimberly region, dating to be confirmed but potentially yira to 50,000 years old.[6]

The boomerang was first encountered by European people at Farm Cove (Port Jackson), Australia, in December 1804, when a weapon was witnessed during a tribal skirmish:[7]

... the white spectators were justly astonished at the dexterity and incredible force with which a bent, edged waddy resembling slightly a turkish scimytar, was thrown by Bungary, a native distinguished by his remarkable courtesy. The weapon, thrown at 20 or 30 yards [18 or 27 m] distance, twirled round in the air with astonishing velocity, and alighting on the right arm of one of his opponents, actually rebounded to a distance not less than 70 or 80 yards [64 or 73 m], leaving a horrible contusion behind, and exciting universal admiration.

In 1822 it was described in detail wer recorded as a "bou-mar-rang", in the language of the Turuwal people (a sub-group of the Dharug) of the Georges River near Port Jackson. The Turawal used other words for their hunting sticks but used "boomerang" to refer to a returning throw-stick.[5]

Given name

[edit | edit source]The name 'Kylie' is now in common use in Australia as a girl's name.[8][2]

Engineering

[edit | edit source]Kylies are the earliest known examples of a man-made object showing heavier than air flight, whereas dowaks are just a projectile.

The kylie has a special curved aerofoil shape so that it flies in a curve wer returns to a skillful thrower if it doesn't hit its target (it would be a complete fluke if it hit its target wer then returned to the thrower).

A kylie has two (or in some modern examples karro than two) wings connected at an angle. Each wing is shaped as an airfoil wer arranged so that the spinning creates unbalanced aerodynamic forces that curve its path so that it travels in an elliptical path wer returns to its point of origin when thrown correctly.

An early explanation of how it worked was by Sir Thomas Mitchell, who was given the task of assessing the fighting capabilities of Aboriginal mobs during his many explorations. He wrote, in 1846, a detailed account of how a boomerang returns, describing it as the effect of air pressure il the two opposed surfaces (produced by the twist in the wood at the tips of the boomerang) combined with the spinning motion produced by the throw.[5]

As the wing rotates wer the boomerang moves through the air, nidja creates airflow over the wings wer nidja creates lift il both "wings". However, during one-half of each blade's rotation, it sees a higher airspeed, because the rotation tip-speed wer the forward speed add, wer when it is in the other half of the rotation, the tip speed subtracts from the forward speed. Thus if thrown nearly upright each blade generates karro lift at the top than the bottom.[9]

While it might be expected that nidja would cause the boomerang to tilt around the axis of travel, because the boomerang has significant angular momentum the gyroscopic effect causes the plane of rotation to tilt about an axis that is 90 degrees to the direction of flight, wer nidja is what curves the flight in such a way that it will tend to return.[9]

Thus gyroscopic precession is what makes the boomerang return to the thrower when thrown correctly. Nidja is also what makes the boomerang fly straight yira into the air when thrown incorrectly. With the exception of long-distance boomerangs, they should not be thrown sidearm or like a Frisbee, but rather thrown with the long axis of the wings rotating in an almost-vertical plane.

Some Aboriginal boomerangs had a dimpled surface, for the same reason as golf balls are dimpled, to provide extra lift to keep them in the air longer.

Sport

[edit | edit source]Boomerangs are now thrown as a sport.[10] In international competition, a world cup is organized by the International Federation of Boomerang Association wer now held every second year. In 1991 wer again in 2014 the competition was held in Perth.[11] Boomerangs are again being made in Perth, by Rangs Boomerangs at 18 Cross Road, Bedfordale WA 6112.[12]

Competition disciplines

[edit | edit source]Modern boomerang tournaments usually involve some or yennar of the events listed below. In yennar disciplines the boomerang must travel at least 20 m from the thrower. Throwing takes place individually. The thrower stands at the centre of concentric rings marked il an open field.

Events include:

- Aussie Round: considered by many to be the ultimate test of boomeranging skills. The boomerang should ideally cross the 50 m circle wer come right back to the centre. Each thrower has five attempts. Points are awarded for distance, accuracy wer the catch.

- Accuracy: points are awarded according to how close the boomerang lands to the centre of the rings. The thrower must not touch the boomerang after it has been thrown. Each thrower has five attempts. In major competitions there are two accuracy disciplines: Accuracy 100 wer Accuracy 50.

- Endurance: points are awarded for the number of catches achieved in 5 minutes.

- Fast Catch: the time taken to throw wer catch the boomerang five times. The winner has the fastest timed catches.

- Trick Catch/Doubling: points are awarded for trick catches behind the back, between the feet, wer so on. In Doubling the thrower has to throw two boomerangs at the same time wer catch them in sequence in a special way.

- Consecutive Catch: points are awarded for the number of catches achieved before the boomerang is dropped. The event is not timed.

- MTA 100 (Maximal Time Aloft 100): points are awarded for the length of time spent by the boomerang in the air. The field is normally a circle measuring 100 m. An alternative to nidja discipline, without the 100 m restriction is called MTA unlimited.

- Long Distance: the boomerang is thrown from the middle point of a 40 m baseline. The furthest distance travelled by the boomerang away from the baseline is measured. Il returning the boomerang must cross the baseline again but does not have to be caught.

- Juggling: as with Consecutive Catch, only with two boomerangs. At any given time keny boomerang must be in the air.

Ngiyan waarnk - References

[edit | edit source]- ↑ A Noongar word for ‘smoke’ finds a place in science. University News. University of Western Australia. Pub 6 March 2009. Retrieved 12 December 2016

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Mark Gwynn. The evolution of a word–the case of ‘Kylie’. Ozwords. Pub 12 December 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2016

- ↑ Olman Walley. Hilton Primary School. 2016

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Peter Bindon (previously Curator of Anthropology at the WA Museum for 20 years). "The Ancient Egyptian Hunt". Talk at the Ancient Egyptian Society of WA (AESWA). Wednesday 6 November 2019

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Tony Butz. What is a Boomerang?. Boomerang Association of Australia. Pub 15 September 1961. Retrieved 4 December 2016

- ↑ Erin Parke. Aboriginal artwork in the Kimberley could be among oldest in the world, scientists say. ABC News. Pub 3 November 2015. Retrieved 6 December 2016

- ↑ SYDNEY. The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser. Sun 23 Dec 1804. Page 2. National Library of Australia. Retrieved 4 December 2016

- ↑ Morris, Edward Ellis (1898). Austral English: a dictionary of Australasian words, phrases, and usages. MacMillan & Co

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 C. R. Nave. Boomerang as Vector Rotation Example. HyperPhysics. Georgia State University. Retrieved 6 December 2016

- ↑ Claire Nichols. It's all coming back - the art of boomerang throwing. 720 ABC Perth. Pub 10 February 2015. Retrieved 5 December 2016

- ↑ World Team Cup History. International Federation of Boomerang Association. Retrieved 4 December 2016

- ↑ Rangs Boomerangs. Retrieved 5 December 2016